Diagnostic tests that help rule out other diseases include:

- Urinalysis

- Urine culture

- Cystoscopy

- Biopsy of the bladder wall

- Distention of the bladder under anesthesia

- Urine cytology

- Laboratory examination of prostate secretions.

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a condition that results in recurring discomfort or pain in the bladder and the surrounding pelvic region. The symptoms vary from case to case and even in the same individual. People may experience mild discomfort, pressure, tenderness, or intense pain in the bladder and pelvic area. Symptoms may include an urgent need to urinate, a frequent need to urinate, or a combination of these symptoms. Pain may change in intensity as the bladder fills with urine or as it empties. Women’s symptoms often get worse during menstruation. They may sometimes experience pain during vaginal intercourse.

Because Interstitial Cystitis varies so much in symptoms and severity, most researchers believe it is not one, but several diseases. In recent years, scientists have started to use the term painful bladder syndrome (PBS) to describe cases with painful urinary symptoms that may not meet the strictest definition of Interstitial Cystitis. The term Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome includes all cases of urinary pain that can’t be attributed to other causes, such as infection or urinary stones.

The term interstitial cystitis, or IC, is used alone when describing cases that meet all of the Interstitial Cystitis criteria established by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

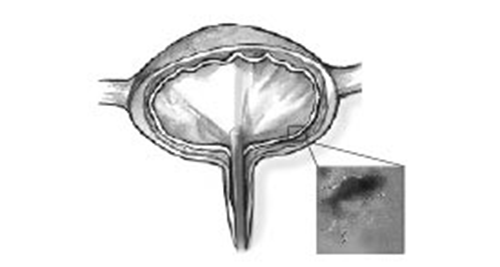

In Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome, the bladder wall may be irritated and become scarred or stiff. Glomerulations—pinpoint bleeding caused by recurrent irritation—often appear on the bladder wall. Hunner’s ulcers are present in 10 percent of people with Interstitial Cystitis. Some people with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome find that their bladder cannot hold much urine, which increases the frequency of urination. Frequency, however, is not always specifically related to bladder size; many people with severe frequency have normal bladder capacity. People with severe cases of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome may urinate as many as 60 times a day, including frequent nighttime urination, also called nocturia. Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome is far more common in women than in men.

Some of the symptoms of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome resemble those of bacterial infection, but medical tests reveal no organisms in the urine of people with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome. Furthermore, people with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome do not respond to antibiotic therapy. Researchers are working to understand the causes of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome and to find effective treatments.

In recent years, researchers have isolated a substance found almost exclusively in the urine of people with Interstitial Cystitis. They have named the substance antiproliferative factor, or APF, because it appears to block the normal growth of the cells that line the inside wall of the bladder. Researchers anticipate that learning more about APF will lead to a greater understanding of the causes of Interstitial Cystitis and to possible treatments.

Many women with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome have other conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia. Scientists believe Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome may be a bladder manifestation of a more general condition that causes inflammation in various organs and parts of the body.

Researchers are beginning to explore the possibility that heredity may play a part in some forms of Interstitial Cystitis. In a few cases, Interstitial Cystitis has affected a mother and a daughter or two sisters, but it does not commonly run in families.

Because symptoms are similar to those of other disorders of the bladder and there is no definitive test to identify Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome , doctors must rule out other treatable conditions before considering a diagnosis of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome .

The most common of these diseases in both sexes are urinary tract infections and bladder cancer. In men, common diseases include chronic prostatitis or chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome is not associated with any increased risk of developing cancer.

The diagnosis of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome in the general population is based on the presence of pain related to the bladder, usually accompanied by frequency and urgency absence of other diseases that could cause the symptoms.

Diagnostic tests that help rule out other diseases include:

Examining urine with a microscope and culturing the urine can detect and identify the primary organisms that are known to infect the urinary tract and that may cause symptoms similar to Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome. A urine sample is obtained either by catheterization or by the clean catch method. For a clean catch, the patient washes the genital area before collecting urine midstream in a sterile container. White and red blood cells and bacteria in the urine may indicate an infection of the urinary tract, which can be treated with an antibiotic. If urine is sterile for weeks or months while symptoms persist, the doctor may consider a diagnosis of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome .

Although not commonly done, in men, the doctor might obtain prostatic fluid and examine it for signs of a prostate infection, which can then be treated with antibiotics.

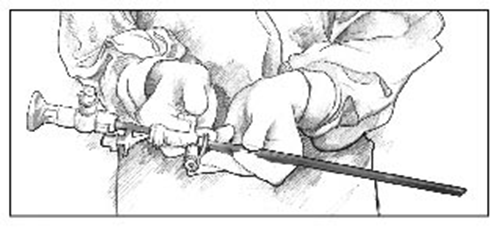

The doctor may perform a cystoscopic examination in order to rule out bladder cancer. During cystoscopy, the doctor uses a cystoscope—an instrument made of a hollow tube about the diameter of a drinking straw with several lenses and a light—to see inside the bladder and urethra. The doctor might also distend or stretch the bladder to its capacity by filling it with a liquid or gas. Because bladder distention is painful for people with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome, they must be given some form of anesthesia for the procedure.

A biopsy is a tissue sample that can be examined with a microscope. Tissue samples of the bladder and urethra may be removed during a cystoscopy. A biopsy helps rule out bladder cancer.

Researchers are investigating and validating some promising biomarkers such as APF, some cytokines, and other growth factors. These might provide more reliable diagnostic markers for Interstitial Cystitis and lead to more focused treatment for the disease.

Scientists have not yet found a cure for Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome, nor can they predict who will respond best to which treatment. Symptoms may disappear with a change in diet or treatments or without explanation. Even when symptoms disappear, they may return after days, weeks, months, or years. Scientists do not know why.

Because the causes of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome are unknown, current treatments are aimed at relieving symptoms. Many people are helped for variable periods by one or a combination of treatments. As researchers learn more about Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome, the list of potential treatments will change, so patients should discuss their options with a doctor.

Healthy Life Harvest™ IC Aloe Vera™ is one of the oldest and most effective all natural products available for assisting with Interstitial Cystitis symptoms.

Though it has not been approved by the FDA, the company has completed a double blind placebo study in which over 80% of sufferers where helped with their Interstitial Cystitis symptoms.

This company has been around since 1992 at which time the founder of Healthy Life Harvest™ discovered the connection between Interstitial Cystitis and a very special species of Aloe Vera now called the IC Aloe®.

Many people with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome have noted an improvement in symptoms after a bladder distention has been done to diagnose the condition. In many cases, the procedure is used as both a diagnostic test and initial therapy. Researchers are not sure why distention helps, but some believe it may increase capacity and interfere with pain signals transmitted by nerves in the bladder. Symptoms may temporarily worsen 4 to 48 hours after distention, but should return to predistention levels or improve within 2 to 4 weeks.

During a bladder instillation, also called a bladder wash or bath, the bladder is filled with a solution that is held for varying periods of time, averaging 10 to 15 minutes, before being emptied.

The only drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for bladder instillation is dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, brand name Rimso-50). DMSO treatment involves guiding a narrow tube called a catheter up the urethra into the bladder. A measured amount of DMSO is passed through the catheter into the bladder, where it is retained for about 15 minutes before being expelled. Treatments are given every week or two for 6 to 8 weeks and repeated as needed. Most people who respond to DMSO notice improvement 3 or 4 weeks after the first 6- to 8-week cycle of treatments.

One bothersome side effect of DMSO treatments is a garlic-like taste and odor on the breath and skin that may last up to 7 hours after treatment. Long-term treatment has caused cataracts in animal studies, but this side effect has not appeared in humans. Blood tests, including a complete blood count and kidney and liver function tests, should be done about every 6 months.

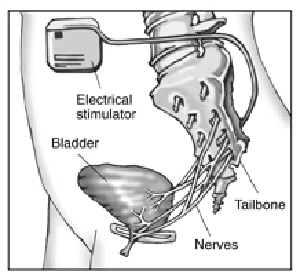

Mild electrical pulses can be used to stimulate the nerves to the bladder—either through the skin or with an implanted device. The method of delivering impulses through the skin is called transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS). With TENS, mild electric pulses enter the body for minutes to hours, two or more times a day either through wires placed on the lower back or just above the pubic area—between the navel and the pubic hair—or through special devices inserted into the vagina in women or into the rectum in men. Although scientists do not know exactly how TENS relieves pelvic pain, it has been suggested that the electrical pulses may increase blood flow to the bladder, strengthen pelvic muscles that help control the bladder, or trigger the release of substances that block pain.

TENS is relatively inexpensive and allows people with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome to take an active part in treatment. Within some guidelines, the patient decides when, how long, and at what intensity TENS will be used. It has been most helpful in relieving pain and decreasing frequency in people with Hunner’s ulcers. Smokers do not respond as well as nonsmokers. If TENS is going to help, improvement is usually apparent in 3 to 4 months.

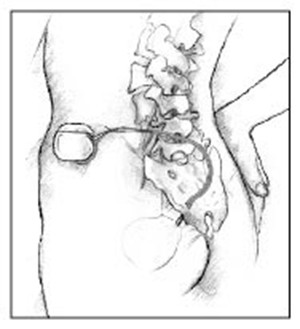

If TENS is effective in relieving symptoms, a person may consider having a device implanted that delivers regular impulses to the bladder. A wire is placed next to the tailbone and attached to a permanent stimulator under the skin.

No scientific evidence links diet to Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome, but many doctors and patients find that alcohol, tomatoes, spices, chocolate, caffeinated and citrus beverages, and high-acid foods may contribute to bladder irritation and inflammation. Some people also note that their symptoms worsen after eating or drinking products containing artificial sweeteners. Eliminating various items from the diet and reintroducing them one at a time may determine which, if any, affect a person’s symptoms.

However, maintaining a varied, well-balanced diet is important.

Many people feel smoking makes their symptoms worse. How the by-products of tobacco that are excreted in the urine affect Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome is unknown. Smoking, however, is the major known cause of bladder cancer. One of the best things smokers can do for their bladder and their overall health is to quit.

Many patients feel that gentle stretching exercises help relieve Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome symptoms.

People who have found adequate relief from pain may be able to reduce frequency by using bladder training techniques. Methods vary, but basically patients decide to void—empty their bladder—at designated times and use relaxation techniques and distractions to keep to the schedule. Gradually, they try to lengthen the time between scheduled voids. A diary in which to record voiding times is helpful in keeping track of progress.

Surgery should be considered only if all available treatments have failed and the pain is disabling. Many approaches and techniques are used, each of which has advantages and complications that should be discussed with a surgeon. A doctor may recommend consulting another surgeon for a second opinion before taking this step. Most surgeons are reluctant to operate because some people still have symptoms after surgery.

People considering surgery should discuss the potential risks and benefits, side effects, and long- and short-term complications with a surgeon, their family, and people who have already had the procedure. Surgery requires anesthesia, hospitalization, and weeks or months of recovery. As the complexity of the procedure increases, so do the chances for complications and failure.

People should check with their doctor to locate a surgeon experienced in performing specific procedures.

Two procedures—fulguration and resection of ulcers—can be done with instruments inserted through the urethra. Fulguration involves burning Hunner’s ulcers with electricity or a laser. When the area heals, the dead tissue and the ulcer fall off, leaving new, healthy tissue behind. Resection involves cutting around and removing the ulcers. Both treatments are done under anesthesia and use special instruments inserted into the bladder through a cystoscope. Laser surgery in the urinary tract should be reserved for people with Hunner’s ulcers and should be done only by doctors with the special training and expertise needed to perform the procedure.

Another surgical treatment is augmentation, which makes the bladder larger. In most of these procedures, scarred, ulcerated, and inflamed sections of the patient’s bladder are removed, leaving only the base of the bladder and healthy tissue. A piece of the patient’s colon—large intestine—is then removed, reshaped, and attached to what remains of the bladder. After the incisions heal, the patient may void less frequently. The effect on pain varies greatly; Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome can sometimes recur on the segment of colon used to enlarge the bladder.

Even in carefully selected patients—those with small, contracted bladders—pain, frequency, and urgency may remain or return after surgery, and they may have additional problems with infections in the new bladder and difficulty absorbing nutrients from the shortened colon. Some patients become incontinent, while others cannot void at all and must insert a catheter into the urethra to empty the bladder.

Bladder removal, called a cystectomy, is another, infrequently used surgical option. Once the bladder has been removed, different methods can be used to reroute the urine. In most cases, ureters are attached to a piece of colon that opens onto the skin of the abdomen. This procedure is called a urostomy and the opening is called a stoma. Urine empties through the stoma into a bag outside the body. Some urologists are using a second technique that also requires a stoma but allows urine to be stored in a pouch inside the abdomen. At intervals throughout the day, the patient puts a catheter into the stoma and empties the pouch. Patients with either type of urostomy must be very careful to keep the area in and around the stoma clean to prevent infection. Serious potential complications may include kidney infection and small bowel obstruction.

A third method to reroute urine involves making a new bladder from a piece of the patient’s colon and attaching it to the urethra. After healing, the patient may be able to empty the newly formed bladder by voiding at scheduled times or by inserting a catheter into the urethra. Only a few surgeons have the special training and expertise needed to perform this procedure.

Even after total bladder removal, some patients still experience variable Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome symptoms in the form of phantom pain. Therefore, the decision to undergo a cystectomy should be made only after testing all alternative methods and seriously considering the potential outcome.

Cancer

No evidence exists that Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome increases the risk of bladder cancer.

Pregnancy

Researchers have little information about pregnancy and Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome but believe that the disorder does not affect fertility or the health of the fetus. Some women find that their Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome goes into remission during pregnancy, while others experience a worsening of their symptoms

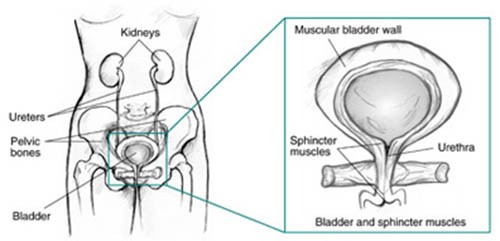

Parts of the bladder control system. The bladder is a balloon-shaped organ that stores and releases urine. It sits in the pelvis. The bladder is supported and held in place by pelvic muscles. The bladder itself is a muscle.

The tube that carries urine from your body is called the urethra. Ring-like muscles called sphincters help keep the urethra closed so urine doesn’t leak from the bladder before you’re ready to release it.

Parts of the bladder control system.

Several body systems must work together to control the bladder.

Bladder control problems can start when any one of these features is not working properly.

Parts of the bladder control system: nerves and brain.

Your bladder is a balloon-shaped organ where your body holds urine. When you have a bladder problem, you may notice certain signs or symptoms.

Some people may have pain without urgency or frequency. Others have urgency and frequency without pain

Your doctor will ask you questions and run tests to find the cause of your bladder problems. Usually, the doctor will find that you have either an infection or an overactive bladder. But urgency, frequency, and pain are not always caused by infection.

Sometimes the cause is hard to find. If all the test results are normal and all other diseases are ruled out, your doctor may find that you have Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome.

Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome affects both men and women, but it is nine times more common in women. It can occur at any age, but it is most common in middle age.

People with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome rarely have bladder pain all the time. The pain usually comes and goes as the bladder fills and then empties. The pain may go away for weeks or months and then return. People with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome sometimes refer to an attack of bladder pain as a flare or flare-up. Stress may bring on a flare-up of symptoms in someone who has Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome. But stress does not cause a person to get Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome.

Finding the cause of bladder pain may require several tests.

Urine sample. At the doctor’s office, you may be given a cup to take into the bathroom. A health professional will give you instructions for collecting urine in the cup. If you have a bladder infection, your urine will contain germs and maybe pus that can be seen with a microscope. The doctor can treat an infection by giving you antibiotics. If your urine is germ-free for weeks or months, but you still have bladder pain, the doctor may decide that you have Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome.

Cystoscope

Bladder exam with a scope. The doctor may do an exam to see the inside of your bladder using a cystoscope. The tip of this long, thin scope is guided gently up the urethra and into the bladder. The doctor can then see inside your bladder by looking through an eyepiece at the other end of the scope. The doctor may fill the bladder with a liquid. When the bladder is filled, the doctor can see the inner wall better. After the exam, you will release the liquid naturally through your urethra.

Inside the Bladder

What does the doctor learn from looking inside your bladder? This exam can help the doctor make sure cancer is not in the bladder. If you have a bladder stone, the doctor can take it out through the cystoscope.

Symptom scale. Your doctor may ask you to fill out a form with a series of questions about how you feel. The symptom scale cannot be used to diagnose Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome but may allow your doctor to better understand how you are responding to treatment.

While tests may aid your doctor in making a diagnosis of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome, a careful review of your symptoms and a physical exam in the office are generally the most important parts of the evaluation.

Not all bladder control problems are alike. Some problems are caused by weak muscles, while others are caused by damaged nerves. Sometimes the cause may be a medicine that dulls the nerves.

To help solve your problem, your doctor or nurse will try to identify the type of incontinence you have. It may be one or more of the following six types.

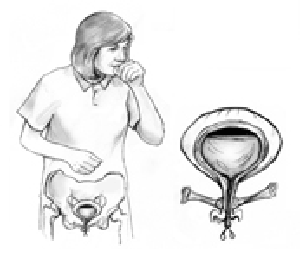

In stress incontinence, weak pelvic muscles can let urine escape when a cough or other action puts pressure on the bladder.

Urine leakage has many possible causes.

Diseases and conditions that can damage the nerves include

Trauma that can damage the nerves includes

Talking about bladder control problems is not easy for some people. You may feel embarrassed to tell your doctor. But talking about the problem is the first step in finding an answer. Also, you can be sure your doctor has heard it all before. You will not shock or embarrass your doctor or nurse.

You can prepare for your visit to the doctor’s office by gathering the information your doctor will need to understand your problem. Make a list of the medicines you are taking. Include prescription medicines and those you buy over the counter, like aspirin or antacid. List the fluids you drink regularly, including sodas, coffee, tea, and alcohol. Tell the doctor how much of each drink you have in an average day.

You will need to find a doctor who is skilled in helping women with urine leakage. If your primary doctor shrugs off your problem as normal aging, for example, ask for a referral to a specialist—an urogynecologist or a urologist who specializes in treating female urinary problems. You may need to be persistent, or you may need to look to organizations to help locate a doctor in your area.

Make a note of any recent surgeries or illnesses you have had. Let the doctor know how many children you have had. These events may or may not be related to your bladder control problem.

Finally, keep track of the times when you have urine leakage. Note what you were doing at the time. Were you coughing, laughing, sneezing, or exercising? Did you have an uncontrollable urge to urinate when you heard running water?

The doctor will give you a physical exam to look for any health issues that may be causing your bladder control problem. Checking your reflexes can show possible nerve damage. You will give a urine sample so the doctor can check for a urinary tract infection. For women, the exam may include a pelvic exam. Tests may also include taking an ultrasound picture of your bladder. Or the doctor may examine the inside of your bladder using a cystoscope, a long, thin tube that slides up into the bladder through the urethra.

Your exam may include one or more tests that involve filling the bladder with warm fluid to measure the pressure at which leakage may occur. One simple test is called a stress test. You simply relax and then cough strongly to see if urine escapes.

Any medical test can be uncomfortable. Bladder testing may sound embarrassing, but the health professionals who perform the tests will try to make you feel comfortable and give you as much privacy as possible.

Your doctor will likely offer several treatment choices. Some treatments are as simple as changing some daily habits. Other treatments require taking medicine or using a device. If nothing else seems to work, surgery may help a woman with stress incontinence regain her bladder control.

Talk with your doctor about which treatments might work best for you.

Many women prefer to try the simplest treatment choices first. Kegel exercises strengthen the pelvic muscles and don’t require any equipment. Once you learn how to “Kegel,” you can Kegel anywhere. The trick is finding the right muscles to squeeze. Your doctor or nurse can help make sure you are squeezing the right muscles. Your doctor may refer you to a specially trained physical therapist who will teach you to find and strengthen the sphincter muscles. Learning when to squeeze these muscles can also help stop the bladder spasms that cause urge incontinence. After about 6 to 8 weeks, you should notice that you have fewer leaks and more bladder control.

By keeping track of the times you leak urine, you may notice certain times of day when you are most likely to have an accident. You can use that information to make planned trips to the bathroom ahead of time to avoid the accident. Once you have established a safe pattern, you can build your bladder control by stretching out the time between trips to the bathroom. By forcing your pelvic muscles to hold on longer, you make those muscles stronger.

You may notice that certain foods and drinks cause you to urinate more often. You may find that avoiding caffeinated drinks like coffee, tea, or cola helps your bladder control. You can choose the decaf version of your favorite drink. Make sure you are not drinking too much fluid because that will cause you to make a large amount of urine. If you are bothered by nighttime urination, drink most of your fluids during the day and limit your drinking after dinner. You should not, however, avoid drinking fluids for fear of having an accident. Some foods may irritate your bladder and cause urgency. Talk with your doctor about diet changes that might affect your bladder.

Extra body weight puts extra pressure on your bladder. By losing weight, you may be able to relieve some of that pressure and regain your bladder control.

No medications are approved to treat stress urinary incontinence. But if you have an overactive bladder, your doctor may prescribe a medicine that can calm muscles and nerves. Medicines for overactive bladder come as pills, liquid, or a patch.

Medicines for other conditions also can affect the nerves and muscles of the urinary tract in different ways. Pills to treat swelling—edema—or high blood pressure may increase urine output and contribute to bladder control problems.

A pessary is a plastic ring, similar to a contraceptive diaphragm, which is worn in the vagina. It will help support the walls of the vagina, lifting the bladder and nearby urethra, leading to less stress leakage. A doctor or nurse can fit you with the best shape and size pessary for you and teach you how to care for it. Many women use a pessary only during exercise while others wear their pessary all day to reduce stress leakage. If you use a pessary, you should see your doctor regularly to check for small scrapes in the vagina that can result from using the device.

A device can be placed under your skin to deliver mild electrical pulses to the nerves that control bladder function. Electrical stimulation of the nerves that control the bladder can improve symptoms of urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence, as well as bladder emptying problems, in some people. This treatment is usually offered to patients who cannot tolerate or do not benefit from medications. At first, your doctor will use a device outside your body to deliver stimulation through a wire implanted under your skin to see if the treatment relieves your symptoms. If the temporary treatment works well for you, you may be able to have a permanent device implanted that delivers stimulation to the nerves in your back, much like a pacemaker. The electrodes in the permanent device are placed in your lower back through a minor surgical procedure. You may need to return to the doctor for adjustments to find the right setting that controls your bladder symptoms.

Doctors may suggest surgery to improve bladder control if other treatments have failed. Surgery helps only stress incontinence. It won’t work for urge incontinence. Many surgical options have high rates of success.

Most stress incontinence problems are caused by the bladder neck dropping toward the vagina. To correct this problem, the surgeon raises the bladder neck or urethra and supports it with a ribbon-like sling or web of strings attached to a muscle or bone. The sling holds up the bottom of the bladder and the top of the urethra to stop leakage.

Surgery to lift the bladder may use a web of strings (left) or a ribbon like sling (right) to support the bladder neck and urethra.

If your bladder does not empty well as a result of nerve damage, you might leak urine. This condition is called overflow incontinence. You might use a catheter to empty your bladder. A catheter is a thin tube you can learn to insert through the urethra into the bladder to drain urine. You may use a catheter once in a while, a few times a day, or all of the time. If you use the catheter all the time, it will drain urine from your bladder into a bag you can hang from your leg. If you use a catheter all the time, you should watch for possible infections.

Women of all ages have bladder control problems. You may think bladder control problems are something that happens when you get older. The truth is that women of all ages have urine leakage. The problem is also called incontinence. Men leak urine too, but the problem is more common in women.

Urine leakage may be a small bother or a large problem. About half of adult women say they have had urine leakage at one time or another. Many women say it’s a daily problem.

Urine leakage is more common in older women, but that doesn’t mean it’s a natural part of aging. You don’t have to “just live with it.” You can do something about it and regain your bladder control.

Incontinence is not a disease. But it may be a sign that something is wrong. It’s a medical problem, and a doctor or nurse can help.

Several treatments are available to help with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome. No one treatment works for everyone. You may have to try two or three treatments before you find a plan that works for you. Be patient. Don’t give up if the first thing you try doesn’t work.

Some people with Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome find that certain foods or drinks bring on their symptoms. Others find no link between symptoms and what they eat.

Keeping a food diary might help you identify foods that cause flare-ups.

Learning what foods cause symptoms for you may require some trial and error. Keep a food diary and note the times you have bladder pain. The diary might reveal that your flare-ups always happen, for example, after you eat tomatoes or oranges due to the amount of acid that gets into the urine.

If you make changes to your diet, remember to eat a variety of healthy foods.

Bladder retraining is a way to help your bladder hold more urine. People with bladder pain often get in the habit of using the bathroom as soon as they feel pain or urgency. They then feel the need to go before the bladder is really full. The body may get used to frequent voiding. Bladder retraining helps your bladder hold more urine before signaling the urge to urinate.

Keep a bladder diary to track how you are doing. Start by noting the times when you void. Note how much time goes by between voids. For example, you may find that you return to the bathroom every 40 minutes.

Try to stretch out the time between voids. If you usually void every 40 minutes, try to wait at least 50 minutes before you go to the bathroom.

If your bladder becomes painful, you may use the bathroom. But you may find that your first urge to use the bathroom goes away if you ignore it. Find ways to relax or distract yourself when the first urge strikes.

After a few days, you may be able to stretch the time out to 60 or 70 minutes, and you may find that the urge to urinate does not return as soon.

If you have Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome, you may feel the last thing you want to do is exercise. But many people feel that easy activities like walking or gentle stretching exercises help relieve symptoms.

Your doctor or nurse may suggest pelvic exercises. The pelvic muscles hold the bladder in place and help control urination. The first step is to find the right muscle to squeeze. A doctor, nurse, or physical therapist can help you. One way to find the muscles is to imagine that you are trying to stop passing gas. Squeeze the muscles you would use. If you sense a “pulling” feeling, you have found the right muscles for pelvic exercises.

You may need exercises to strengthen those muscles so that it’s easier to hold in urine. Or you may need to learn to relax your pelvic muscles if tense muscles are part of your bladder pain.

Some physical therapists specialize in helping people with pelvic pain. Ask your doctor or nurse to help you find a professional trained in pelvic floor physical therapy.

Stress doesn’t cause Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome . But stress can trigger painful flare-ups in someone who has Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome . Learning to reduce stress in your life by making time for relaxation every day may help control some symptoms of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome .

The doctor may stretch the bladder by filling it with liquid after you have been given medicine to make you sleep. Some patients have said their symptoms were helped after this exam.

If you have tried diet changes, exercise, and medicines and nothing seems to help, you may wish to think about nerve stimulation. This treatment sends mild electrical pulses to the nerves that control the bladder.

If you have tried diet changes, exercise, and medicines and nothing seems to help, you may wish to think about nerve stimulation. This treatment sends mild electrical pulses to the nerves that control the bladder.

At first, you may try a system that sends the pulses through electrodes placed on your skin. If this therapy works for you, you may consider having a device put in your body. The device works something like a pacemaker, delivering small pulses of electricity to the nerves around the bladder.

For some patients, nerve stimulation relieves bladder pain as well as urinary frequency and urgency. For others, the treatment relieves frequency and urgency but not pain. For still other patients, it does not work.

Scientists are not sure why nerve stimulation works. Some believe that the electrical pulses block the pain signals carried in the nerves. If your brain doesn’t receive the nerve signal, you don’t feel the pain. Others believe that the electricity releases endorphins, which are hormones that block pain naturally.

Implanted nerve stimulation device.

As a last resort, your doctor might suggest surgery to remove part or all of the bladder. Surgery does not cure the pain of Interstitial Cystitis/Painful Bladder Syndrome in all cases, but if you have tried every other option and your pain is still unbearable, surgery might be considered.

Talk with your doctor and family about the possible benefits and side effects.

Points to Remember

| cancer | depression |

| crippling arthritis | diverticulitis |

| diabetes | multiple sclerosis |

| interstitial cystitis | stroke |

| spinal cord injury | other_____________________ |

| urinary infection |

This diary will help you and your health care team figure out the causes of your bladder control trouble. The “sample” line shows you how to use the diary.

Your name: ________________________________________________________

Date: ______________________________________________________________

Time | Drinks | Trips to the | Accidental | Did you feel a strong urge to go? | What were you doing at the time? | ||

| What kind? | How much? | How many times? | How much urine? (circle one) | How much? (circle one) | Circle one | Sneezing, exercising |

| Sample | Coffee | 2 cups | X |

| Running | ||

| 6-7 a.m. |

| ||||||

| 7-8 a.m. |

| ||||||

| 8-9 a.m. |

| ||||||

| 9-10 a.m. |

| ||||||

| 10-11 a.m. |

| ||||||

| 11-12 noon |

| ||||||

| 12-1 p.m. |

| ||||||

| 1-2 p.m. |

| ||||||

| 2-3 p.m. |

| ||||||

| 3-4 p.m. |

| ||||||

| 4-5 p.m. |

| ||||||

| 5-6 p.m. |

| ||||||

| 6-7 p.m. |

| ||||||

I used _______ pads today. I used ________ diapers today (write number).

Millions of women experience involuntary loss of urine called urinary incontinence (UI). Some women may lose a few drops of urine while running or coughing. Others may feel a strong, sudden urge to urinate just before losing a large amount of urine. Many women experience both symptoms. UI can be slightly bothersome or totally debilitating. For some women, the risk of public embarrassment keeps them from enjoying many activities with their family and friends. Urine loss can also occur during sexual activity and cause tremendous emotional distress.

Women experience UI twice as often as men. Pregnancy and childbirth, menopause, and the structure of the female urinary tract account for this difference. But both women and men can become incontinent from neurologic injury, birth defects, stroke, multiple sclerosis, and physical problems associated with aging.

Older women experience UI more often than younger women. But incontinence is not inevitable with age. UI is a medical problem. Your doctor or nurse can help you find a solution. No single treatment works for everyone, but many women can find improvement without surgery.

Incontinence occurs because of problems with muscles and nerves that help to hold or release urine. The body stores urine—water and wastes removed by the kidneys—in the bladder, a balloon-like organ. The bladder connects to the urethra, the tube through which urine leaves the body.

During urination, muscles in the wall of the bladder contract, forcing urine out of the bladder and into the urethra. At the same time, sphincter muscles surrounding the urethra relax, letting urine pass out of the body. Incontinence will occur if your bladder muscles suddenly contract or the sphincter muscles are not strong enough to hold back urine. Urine may escape with less pressure than usual if the muscles are damaged, causing a change in the position of the bladder. Obesity, which is associated with increased abdominal pressure, can worsen incontinence. Fortunately, weight loss can reduce its severity.

oughing, laughing, sneezing, or other movements that put pressure on the bladder cause you to leak urine, you may have stress incontinence. Physical changes resulting from pregnancy, childbirth, and menopause often cause stress incontinence. This type of incontinence is common in women and, in many cases, can be treated.

Childbirth and other events can injure the scaffolding that helps support the bladder in women. Pelvic floor muscles, the vagina, and ligaments support your bladder (see figure 2). If these structures weaken, your bladder can move downward, pushing slightly out of the bottom of the pelvis toward the vagina. This prevents muscles that ordinarily force the urethra shut from squeezing as tightly as they should. As a result, urine can leak into the urethra during moments of physical stress. Stress incontinence also occurs if the squeezing muscles weaken.

If you lose urine for no apparent reason after suddenly feeling the need or urge to urinate, you may have urge incontinence. A common cause of urge incontinence is inappropriate bladder contractions. Abnormal nerve signals might be the cause of these bladder spasms.

Urge incontinence can mean that your bladder empties during sleep, after drinking a small amount of water, or when you touch water or hear it running (as when washing dishes or hearing someone else taking a shower). Certain fluids and medications such as diuretics or emotional states such as anxiety can worsen this condition. Some medical conditions, such as hyperthyroidism and uncontrolled diabetes, can also lead to or worsen urge incontinence.

Involuntary actions of bladder muscles can occur because of damage to the nerves of the bladder, to the nervous system (spinal cord and brain), or to the muscles themselves. Multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, and injury—including injury that occurs during surgery—all can harm bladder nerves or muscles.

Overactive bladder occurs when abnormal nerves send signals to the bladder at the wrong time, causing its muscles to squeeze without warning. Voiding up to seven times a day is normal for many women, but women with overactive bladder may find that they must urinate even more frequently.

Specifically, the symptoms of overactive bladder include

People with medical problems that interfere with thinking, moving, or communicating may have trouble reaching a toilet. A person with Alzheimer’s disease, for example, may not think well enough to plan a timely trip to a restroom. A person in a wheelchair may have a hard time getting to a toilet in time. Functional incontinence is the result of these physical and medical conditions. Conditions such as arthritis often develop with age and account for some of the incontinence of elderly women in nursing homes.

Overflow incontinence happens when the bladder doesn’t empty properly, causing it to spill over. Your doctor can check for this problem. Weak bladder muscles or a blocked urethra can cause this type of incontinence. Nerve damage from diabetes or other diseases can lead to weak bladder muscles; tumors and urinary stones can block the urethra. Overflow incontinence is rare in women.

Stress and urge incontinence often occur together in women. Combinations of incontinence—and this combination in particular—are sometimes referred to as mixed incontinence. Most women don’t have pure stress or urge incontinence, and many studies show that mixed incontinence is the most common type of urine loss in women.

Transient incontinence is a temporary version of incontinence. Medications, urinary tract infections, mental impairment, and restricted mobility can all trigger transient incontinence. Severe constipation can cause transient incontinence when the impacted stool pushes against the urinary tract and obstructs outflow. A cold can trigger incontinence, which resolves once the coughing spells cease.

| Stress | Leakage of small amounts of urine during physical movement (coughing, sneezing, exercising). |

| Urge | Leakage of large amounts of urine at unexpected times, including during sleep. |

| Overactive Bladder | Urinary frequency and urgency, with or without urge incontinence. |

| Functional | Untimely urination because of physical disability, external obstacles, or problems in thinking or communicating that prevent a person from reaching a toilet. |

| Overflow | Unexpected leakage of small amounts of urine because of a full bladder. |

| Mixed | Usually the occurrence of stress and urge incontinence together. |

| Transient | Leakage that occurs temporarily because of a situation that will pass (infection, taking a new medication, colds with coughing). |

The first step toward relief is to see a doctor who has experience treating incontinence to learn what type you have. A urologist specializes in the urinary tract, and some urologists further specialize in the female urinary tract. Gynecologists and obstetricians specialize in the female reproductive tract and childbirth. A urogynecologist focuses on urinary and associated pelvic problems in women. Family practitioners and internists see patients for all kinds of health conditions. Any of these doctors may be able to help you. In addition, some nurses and other health care providers often provide rehabilitation services and teach behavioral therapies such as fluid management and pelvic floor strengthening.

To diagnose the problem, your doctor will first ask about symptoms and medical history. Your pattern of voiding and urine leakage may suggest the type of incontinence you have. Thus, many specialists begin with having you fill out a bladder diary over several days. These diaries can reveal obvious factors that can help define the problem—including straining and discomfort, fluid intake, use of drugs, recent surgery, and illness. Often you can begin treatment at the first medical visit.

Your doctor may instruct you to keep a diary for a day or more—sometimes up to a week—to record when you void. This diary should note the times you urinate and the amounts of urine you produce. To measure your urine, you can use a special pan that fits over the toilet rim. You can also use the bladder diary to record your fluid intake, episodes of urine leakage, and estimated amounts of leakage.

If your diary and medical history do not define the problem, they will at least suggest which tests you need.

Your doctor will physically examine you for signs of medical conditions causing incontinence, including treatable blockages from bowel or pelvic growths. In addition, weakness of the pelvic floor leading to incontinence may cause a condition called prolapse, where the vagina or bladder begins to protrude out of your body. This condition is also important to diagnose at the time of an evaluation.

Your doctor may measure your bladder capacity. The doctor may also measure the residual urine for evidence of poorly functioning bladder muscles. To do this, you will urinate into a measuring pan, after which the nurse or doctor will measure any urine remaining in the bladder. Your doctor may also recommend other tests:

By looking at your bladder diary, the doctor may see a pattern and suggest making it a point to use the bathroom at regular timed intervals, a habit called timed voiding. As you gain control, you can extend the time between scheduled trips to the bathroom. Behavioral treatment also includes Kegel exercises to strengthen the muscles that help hold in urine.

The first step is to find the right muscles. One way to find them is to imagine that you are sitting on a marble and want to pick up the marble with your vagina. Imagine sucking or drawing the marble into your vagina.

Try not to squeeze other muscles at the same time. Be careful not to tighten your stomach, legs, or buttocks. Squeezing the wrong muscles can put more pressure on your bladder control muscles. Just squeeze the pelvic muscles. Don’t hold your breath. Do not practice while urinating.

Repeat, but don’t overdo it. At first, find a quiet spot to practice—your bathroom or bedroom—so you can concentrate. Pull in the pelvic muscles and hold for a count of three. Then relax for a count of three. Work up to three sets of 10 repeats. Start doing your pelvic muscle exercises lying down. This is the easiest position to do them in because the muscles do not need to work against gravity. When your muscles get stronger, do your exercises sitting or standing. Working against gravity is like adding more weight.

Be patient. Don’t give up. It takes just 5 minutes a day. You may not feel your bladder control improve for 3 to 6 weeks. Still, most people do notice an improvement after a few weeks.Some people with nerve damage cannot tell whether they are doing Kegel exercises correctly. If you are not sure, ask your doctor or nurse to examine you while you try to do them. If it turns out that you are not squeezing the right muscles, you may still be able to learn proper Kegel exercises by doing special training with biofeedback, electrical stimulation, or both.

Biofeedback uses measuring devices to help you become aware of your body’s functioning. By using electronic devices or diaries to track when your bladder and urethral muscles contract, you can gain control over these muscles. Biofeedback can supplement pelvic muscle exercises and electrical stimulation to relieve stress and urge incontinence.

One of the reasons for stress incontinence may be weak pelvic muscles, the muscles that hold the bladder in place and hold urine inside. A pessary is a stiff ring that a doctor or nurse inserts into the vagina, where it presses against the wall of the vagina and the nearby urethra. The pressure helps reposition the urethra, leading to less stress leakage. If you use a pessary, you should watch for possible vaginal and urinary tract infections and see your doctor regularly.

A variety of bulking agents, such as collagen and carbon spheres, are available for injection near the urinary sphincter. The doctor injects the bulking agent into tissues around the bladder neck and urethra to make the tissues thicker and close the bladder opening to reduce stress incontinence. After using local anesthesia or sedation, a doctor can inject the material in about half an hour. Over time, the body may slowly eliminate certain bulking agents, so you will need repeat injections. Before you receive an injection, a doctor may perform a skin test to determine whether you could have an allergic reaction to the material. Scientists are testing newer agents, including your own muscle cells, to see if they are effective in treating stress incontinence. Your doctor will discuss which bulking agent may be best for you.

In some women, the bladder can move out of its normal position, especially following childbirth. Surgeons have developed different techniques for supporting the bladder back to its normal position. The three main types of surgery are retropubic suspension and two types of sling procedures.

Retropubic suspension uses surgical threads called sutures to support the bladder neck. The most common retropubic suspension procedure is called the Burch procedure. In this operation, the surgeon makes an incision in the abdomen a few inches below the navel and then secures the threads to strong ligaments within the pelvis to support the urethral sphincter. This common procedure is often done at the time of an abdominal procedure such as a hysterectomy.

Sling procedures are performed through a vaginal incision. The traditional sling procedure uses a strip of your own tissue called fascia to cradle the bladder neck. Some slings may consist of natural tissue or man-made material. The surgeon attaches both ends of the sling to the pubic bone or ties them in front of the abdomen just above the pubic bone.

Midurethral slings are newer procedures that you can have on an outpatient basis. These procedures use synthetic mesh materials that the surgeon places midway along the urethra. The two general types of midurethral slings are retropubic slings, such as the transvaginal tapes (TVT), and transobturator slings (TOT). The surgeon makes small incisions behind the pubic bone or just by the sides of the vaginal opening as well as a small incision in the vagina. The surgeon uses specially designed needles to position a synthetic tape under the urethra. The surgeon pulls the ends of the tape through the incisions and adjusts them to provide the right amount of support to the urethra.

If you have pelvic prolapse, your surgeon may recommend an anti-incontinence procedure with a prolapse repair and possibly a hysterectomy.

Side view. Supporting sutures in place following retropubic or transvaginal suspension (left). Sling in place, secured to the pubic bone (center). The ends of the transobturator tape supporting the urethra are pulled through incisions in the groin to achieve the right amount of support (right). The tape ends are removed when the incisions are closed.

Talk with your doctor about whether surgery will help your condition and what type of surgery is best for you. The procedure you choose may depend on your own preferences or on your surgeon’s experience. Ask what you should expect after the procedure. You may also wish to talk with someone who has recently had the procedure. Surgeons have described more than 200 procedures for stress incontinence, so no single surgery stands out as best.

If you are incontinent because your bladder never empties completely—overflow incontinence—or your bladder cannot empty because of poor muscle tone, past surgery, or spinal cord injury, you might use a catheter to empty your bladder. A catheter is a tube that you can learn to insert through the urethra into the bladder to drain urine. You may use a catheter once in a while or on a constant basis, in which case the tube connects to a bag that you can attach to your leg. If you use an indwelling—long-term—catheter, you should watch for possible urinary tract infections.

Many women manage urinary incontinence with menstrual pads that catch slight leakage during activities such as exercising. Also, many people find they can reduce incontinence by restricting certain liquids, such as coffee, tea, and alcohol.

Finally, many women are afraid to mention their problem. They may have urinary incontinence that can improve with treatment but remain silent sufferers and resort to wearing absorbent undergarments, or diapers. This practice is unfortunate, because diapering can lead to diminished self-esteem, as well as skin irritation and sores. If you are relying on diapers to manage your incontinence, you and your family should discuss with your doctor the possible effectiveness of treatments such as timed voiding and pelvic muscle exercises.

Founder of the "IC Aloe Vera"™

Disclaimer:

These statements have not been evaluated by the FDA and are not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, nor is this information meant to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. Results may vary.

1992-PRESENT DAY© HEALTHY LIFE HARVEST,LLC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED